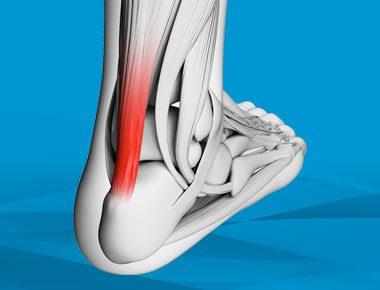

Achilles Tendon Repair Surgery

The Achilles tendon is key to the health of the foot and ankle. Achilles tendon treatment has changed significantly in the last ten years, including more aggressive rehabilitation protocols following surgery.

Hosted by Eric Chehab, MD

Episode Transcript

Episode 2 - Achilles Tendon Repair Surgery

Dr. Eric Chehab:Welcome to IBJI OrthoInform, where we talk all things ortho to help you move better, live better. I'm your host, Dr. Eric Chehab. With OrthoInform, our goal is to provide you with a more in-depth resource regarding common orthopedic procedures that we perform every day. Today, it's my pleasure to welcome Dr. Anand Vora, who will be speaking about the Achilles tendon. As a brief introduction, Dr. Vora graduated with honors from University of Akron in 1994, studying natural sciences, and minoring in chemistry and Spanish. He received his medical degree from Northeastern Ohio University's College of Medicine, from where he also graduated with distinction and was selected to the Alpha Omega Alpha Society.

He came to Chicago in 1998 for his residency training at Northwestern University, and upon his completion of his residency, Dr. Vora completed two years of fellowship training in foot and ankle surgery at Union Memorial Hospital in Johns Hopkins with Dr. Mark Myerson. whose fellowship is considered one of the most prestigious and coveted foot and ankle surgical training programs in the country.

Dr. Vora returned to the Chicago area in 2004, where he joined Illinois Bone and Joint Institute as a foot and ankle specialist. Dr. Vora has published numerous research articles on the foot and ankle and has been recognized regionally and nationally for his research. He acts as a foot and ankle consultant for Arthrex, a leader in orthopedic device manufacturing, and also for the Chicago Fire and the Joffrey Ballet.

Dr. Vora has been active in education, both for industry and as the director of the IBJI foot and ankle fellowship program. He has helped thousands of patients with foot and ankle disorders, and has educated hundreds of surgeons, so they can take better care of their own patients. He is a proven educator, leader and innovator and a gifted surgeon of the foot and ankle.

Anand, welcome to OrthoInform. Thanks so much for taking the time to be here.

Dr. Anand Vora:

Eric, thanks for doing this. Thanks for having me and thanks for the very kind introduction.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Okay. So let's get right into it. The Achilles heel, the proverb of the Achilles heel and the myth of Achilles. Explain to our audience a little bit about the myth of Achilles.

Dr. Anand Vora:

I had a different notion of the Achilles. His mother dipped him in gold as protection, but in the dipping process was holding him by his Achilles heel. And so that's the area of vulnerability. And then they did indeed lacerate his Achilles tendon. And on top of that, I heard from one of our partners, Dr. O'Rourke who trained at Iowa with Leo Ponseti– and Dr. Ponseti is one of the godfathers of pediatric surgery. Um, who said that inWWI? Prisoners of war would have their Achilles tendons cut so that the prisoners couldn't run away.

But interestingly, they'd have to serially cut them in every six months, cut them because the tendon would heal spontaneously, which I wasn't aware of, but we'll get to that also, which is an interesting part.

Dr. Anand Vora:

Right– and that's part of the Ponseti method of taking care of these patients with the Achilles tendon lengthenings.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Yeah. And so, um, it's interesting because it almost seems like there's a design flaw in the Achilles. It seems to work beautifully, until it doesn't. And it's such a sudden unexpected injury that occurs to so many people from young athletic, incredibly well conditioned folks to older people. So what is it about the Achilles tendon that makes it vulnerable to this injury?

Dr. Anand Vora:

Sure. So from an evolutionary standpoint, if we consider that route. In apes, there's no such thing as an Achilles tendon rupture. And so we believe the concept is that evolutionarily, the same bones in the hand and upper extremity are present in the lower extremity. And the Achilles tendon in particular is lengthened as compared to the other similar musculature and upper extremity.

And so that lengthened Achilles tendon, biologically, as compared to the tarsus bones and the bones in the foot appears to put the Achilles tendon at risk because of the way it's developed and because of the relative length of the Achilles tendon compared to the other bones in the foot as compared to the upper extremity.

And so this tendon is at a constant risk of rupture because of its elongated nature and its length in nature. It's like a rubber band that's under constant tension.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

I see. So anytime that that rubber band gets over-tensioned, it's at risk for rupture.

Dr. Anand Vora:

The way it was works is called the eccentric load.

And what that means is that it's actually not at the risk of contracting the muscle. It's at a risk of when it's over lengthened. And at that time, if there's a pressure put through the tendon, the tendons, like a rubber band, that's under stretch, and then there's additional pressure that makes it completely pop.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And then functionally, the Achilles tendon we've always been taught during our residency is the key to the foot and the ankle that, that you have to have a healthy Achilles in order to have a healthy foot and ankle. What is the function of the Achilles tendon?

Dr. Anand Vora:

Well, the Achilles tendon is critical for push-off strength. It's critical for power generation. It's critical to allow for normal gait. And it actually helps not only for push off, but it also helps us land and land our foot softly so that we can decelerate as the foot lands through the gait cycle. So it has a lot of critical functions for normal functional activity, not only for sports and recreational activity, but just normal gait.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So who tears their Achilles?

Dr. Anand Vora: So there's many subsets of patients. There's the athletes that can sometimes tear their Achilles from what we described as overuse, or perhaps a training flaws or training misgivings. Sometimes there's a tight Achilles tendon, genetically that predisposes patients to have that rubber band under more tension than normal.

But the real subset of patients that we see most commonly is our weekend warrior patients, patients that are pretty athletic, that don't train routinely, go out on a weekend and try to play basketball with their kids and are a little bit out of shape. And those are the patients where that rubber band is just ready to give, because it hasn't really been put through its cycle of stretching and shortening routinely.

And so that, out of nowhere, kind of doing something. Can really predispose patients to high risk for rupture.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

In that group of weekend warriors. Are there things that they can do that may help mitigate their risk and lower the risk of developing Achilles or having an Achilles tendon rupture? Developing almost seems like the wrong word, because it's just the snap of your fingers– it's torn.

Dr. Anand Vora:

Yeah. Um, so it's the exception to the rule that patients will have symptoms beforehand. So there are sub-group of patients that will have some preexisting pain in their Achilles tendon, uh, some degeneration of the tendon. The analogy would be like a rope that's kind of stretched out, and so they'll have some inflammation of their attendant and pain beforehand, and those patients, we can do some physical therapy and some preventative stuff to really try to avoid that.

But the remainder it's really difficult to avoid it. It's almost an unavoidable injury, that's an accidental injury. Stretching and doing some stretches for the calf stretches for the Achilles stretches to prevent, uh, stiffness of the ankle certainly can be helpful, but unfortunately there's no real specific preventative measure.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

It is indeed the Achilles heel. It's just vulnerable, no matter what you do, even in the most finely conditioned athlete. But fortunately it's not a, it's a common injury of the foot and ankle, but overall, is there, is it a common injury in general?

Dr. Anand Vora:

It's the definitely the most common tendon ruptured in the foot and ankle and is a very, very common injury universally for orthopedic injuries. Um, and it's an injury that we've learned a lot about and how to manage and we've become very good at managing it, both with surgery and non-surgically.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

I was completely unaware even during my training of the prevalence and how frequently Achilles tendon ruptures are treated non-operatively. And in fact, when I discuss this with patients, they will typically raise an eyebrow. Like, that sounds crazy... because most of the time, at least where I trained in the Northeast, the bias was for surgical repair of the Achilles tendon. Yet there are many places in the country that treat Achilles tendons non-operatively. Is that correct?

Dr. Anand Vora:

That's correct.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Bring us through this a little bit, because this is an interesting point of discussion. First of all, when a patient presents to you, what is the approach to deciding this patient should be treated with surgery or this patient, what should be treated without surgery?

Dr. Anand Vora:

The first response would be that the overall evolution of Achilles tendon treatment has truly changed in the last 10 years. So the pendulum in our party line was that with non-surgical management, Achilles tendon injuries would heal. But they would heal in an elongated state and therefore that push off would not be as good– the rubber band wouldn't have its normal tension. What we've learned is that that actually is not the case with certain types of treatments, specifically using a functional rehabilitation protocol.

So traditionally we put patients in casts, let the tendon heal and kind of deal with what we got. We've learned that using a more aggressive rehab protocol, keeping the ankle moving, but preventing the ankle from going upwards past neutral allows the tendon to still glide, provides the blood supply to the tendon. And so these tendons will heal and sometimes they can heal with very good tension. But the biggest problem is that we don't understand the differences in strength. So we do think that there is anecdotal evidence that strength will be better with surgery. But we do know now for certain that the re-rupture rates with, or without surgery are similarly low.

And so our discussion with patients is really pretty simple. We want to individualize care for that patient. And if a patient's goal is to go out and shoot hoops with their kids on the weekends, maybe go for a jog every once every couple of weeks, those patients will probably do pretty well without surgery. That limited strength that they're going to lose with the surgery without pursuing surgery is probably not going to make a difference in their activities of daily living or their functional activities of life, including sports.

On the flip side, a high level athlete, a collegiate level basketball player, somebody that really depends on that end push off, and that super strength to really get that last additional ability to compete at a high level– We don't know with certainty, but our bias is certainly that strength is going to be better with surgery.

Dr. Eric Chehab: Sure. When we're comparing non-operative and operative treatment for the Achilles, the variables are number one, the activity level of the patient. Number two, the sense that re-rupture, the idea of reinjury, is about equivalent historically. When it was casted, there was a higher re-rupture rate with casting than there was with surgery. And so when coming out of training, we were both probably saying to our patients, there will be a lower re-rupture rate with the surgery, but that's not case with proper functional rehabilitation.

Dr. Anand Vora:

That's correct. We've learned that the re-rupture rate that we used to traditionally tell patients was 20% without surgery. And now we know with, or without surgery that re-rupture rate with proper functional rehabilitation, with non-surgical management, is similar and we're talking less than 5%. But the real difference maker is the strength, that we have to think about that strength.

So the variables that we look at as you suggested for operative or non-operative is patient's level of activity desire their age, there are associated risk factors. For example, if they're smokers, if they're diabetics, if they have other medical problems that make them a little bit more at high risk for surgery, because of the complications of surgery that can occur, we try to lean towards conservative measures, but this is truly a place where our thinking continues to evolve. We've learned a lot that non-surgical management is not wrong, but we still don't know that. The strength and long-term function of non-surgical management will be acceptable to all patients.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Okay. And then if we're going to look at the downsides of non-operative treatment it's strength deficit– potential strength deficit. And then the downside of operative treatment is?

Dr. Anand Vora:

So the downside of operative treatment are simple. All the normal complications and things that can occur with surgery. And those risks are very low. One of the nice things about Achilles tendon surgery and lower extremity surgery in general, is that we can do a lot now through many of our surgical centers and all patient facilities that we utilize, our anesthesiologists are excellent. And so we can do this under a nerve block. That means that the patient does not need a general anesthetic. It's a relatively safe procedure.

So those relative, uh, other comorbid risk factors for surgery are very low. The other risk factors surgically, are infection. Anytime we operate on the foot and ankle, there's a slightly increased risk for infection as compared to other orthopedic areas. And then the risks of injuring a nerve– there is a sensory nerve in that area that can cause some numbness and tingling for patients transiently, usually resolves, it's less than 1% in that situation.

And then finally the biggest and, uh, continued risk is still the risk of re-rupture in those with even non-operative management.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Okay. There are some specific challenges with infection, for instance, infection was always one of the things and wound complications that we were concerned about with surgical treatment in addition to the nerve.

And in addition to the anesthetic and peri-operative potential risks that you've mentioned. But are there specific challenges with infection and wound complications with Achilles tendons, or even though it's single digit percentages, very low percentages that it occurs, but are, are there challenges for treating those complications– and how do you treat those?

Dr. Anand Vora:

Yeah, that's the biggest problem is when we get an Achilles tendon infection, generally speaking, they are very simple. We can treat them conservatively in the office, they're skin infections, and those are easy to take care of. Once every now and then the biggest problem is there's a very thin skin envelope. So the layer between the skin and the tendon is very minimal. And in that rare situation where the infection gets deep into the tendon, that can be a very debilitating problem for patients. And so that incidence is much less than 1%, but in that select patient, it can be a very, very difficult recovery.

And what we need to do is clean out all the bad tendons. Put patients on antibiotics. And then oftentimes we can reconstruct the tendon in other ways, doing tendon transfer procedures. Once the infection resolves.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Take us through the six months of treatment for someone who opts to have their Achilles tendon treated non-operatively.

So what's the first week like, first month, first six months? How do you bring them through?

Dr. Anand Vora:

Yeah, so there's multiple different prescribed protocols for non-operative management. Some of our colleagues in Canada have really described this very well. And I use the Canadian protocol that involves a couple of weeks of casting with the foot pointed down as far as possible, we call that plantar flection– and that allows the two ends of the rubber band to be as close together as possible to start that healing process. Then we put patients in a splint and that splint allows patients to move their ankle up to 90 degrees or to neutral, but it doesn't allow them to move their ankle above that point.

And what that does is allows the rubber band to start moving a little bit, but still not overstretching it during that first six weeks. And during that first six weeks, they're off their foot, no weight on it. Then we make a transition to have them walking in a walking boot for the next six weeks. And we use very simple heel wedges that we progressively remove to bring the ankle from a pointed down position to that neutral position in the boot.

And then around 10 to 12 weeks, patients undergo a rehabilitation process

Dr. Eric Chehab:

After 12 weeks you start doing a more functional recovery with the non-operative treatment.

Dr. Anand Vora:

Correct. Well, we start the functional recovery right away. And I think that one difference is that traditional non-operative measures suggested casting for a period of time, even up to six weeks.

And we've learned that that functional rehab of the patient being out of a cast sooner and moving their ankle, but still immobilizing them to some extent, is what we describe as the quote unquote functional rehab. But their true physical therapy and strengthening and rehabilitation where patients will be able to get their strength back, get their musculature back, start becoming active, really doesn't start until around the 10 to 12 week timeline.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Got it. If I can summarize: First six weeks, non-weightbearing. First two weeks in a cast with the toe pointed down as far as possible, then into a functional brace that allows you to move the ankle, but not too far up so that you're not stretching the rubber band of the Achilles too far.

And then after six weeks you start weight bearing, working on your gait more normal. And then after three months really doing the more functional strength recovery, getting the ankle fully back at that point.

Dr. Anand Vora:

Exactly

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Okay. And let's contrast that with the surgical protocol. So, so let's say I opt to have my Achilles tendon surgically repaired. I want to have as much strength as possible, so that's why I'm opting for that. Take me through the first month, first three months to six months of that recovery.

Dr. Anand Vora:

Absolutely. Within Illinois bone and joint, and within the field of orthopedics in general, the rehab protocols for orthopedic Achilles injuries are extremely variable. We'll speak about our rehab protocol and our rehab protocols seems to be pretty aggressive, but there is some variability in the literature. Our rehab protocol involves an outpatient procedure. Patients have their surgery and they go into a boot right away.

We don't put any immobilization, we want to try and get their ankle moving, so we get a really tight, secure repair at the time of surgery. Patients are in a walker boot, non-weight bearing, but they can remove this boot right away to start moving their ankle actively so we can get the tendon to glide.

What we've learned is the tendon heals, not only by doing the surgery and putting the rubber band together. But letting the tendon move within its sheath and the blood supply around that area then allows for the tendon to heal much quicker and in a much smoother fashion. So the first two weeks they're moving their ankle and in a boot, no weight on it.

And then we allow them to start putting weight on it pretty early at two weeks. Some surgeons will delay that for four to six weeks still. And that's based on their individual protocols. Once we get past that point at around eight weeks, they get into a regular tennis shoe and we really push the physical therapy pretty aggressively.

And during that timeline, the only thing we try to avoid is excessively moving the ankle up past neutral, uh, by pushing the ankle up and that's called passively, but we do allow the patients to move their ankle any way they'd like to just so we can try to get that tendon moving usually at around the 12 week time mark, patients are able to swim, use an elliptical, use a bicycle. By 16 weeks, patients are able to get on a treadmill, even gently jog. Six months is a good landmark where we try to make sure patients are able to run comfortably. By 12 months, we really expect the patients to have similar strength and doing pretty well as compared to the contralateral side.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So again, just to kind of summarize that, it sounds like a couple of weeks, maybe four to six weeks of non-weightbearing. Actively moving the ankle. So the patient's in control of that. They're not having the therapist move their ankle, they're in control of the moving of their ankle up and down. Without limitations, it sounds like, to promote the glide. And then really starting to do some of the walking in a normal tennis shoe by eight weeks and doing some of the functional strengthening pretty much at that point. And, and so it sounds like if you opt for a surgical treatment, you may actually be ahead of the game in terms of your recovery, getting back on your feet, than if you opt for non-operative treatment. Is that correct?

Dr. Anand Vora:

That's correct. But I think that one of the things, again, just to point out is that depends on the surgeon's rehab protocol. Because some surgeons still may be very slow in their rehab protocol and rightfully so. But the literature would certainly support, and our experience certainly supports in the short term, operative treatment seems to have a more aggressive ability to rehab patients, which is what we'd expect because we're able to place the tendon exactly where we want it under normal tension, rather than hoping for indirect opposition to the tendon using nonsense surgical management.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

If someone does rupture their Achilles, they come into your office and you discuss these variables of your activity, your desire for full strength versus the need for full strength and wound complications.

And, and when you weigh it all, if they do opt for surgery, is there a certain timeframe that you want to get the surgery surgery done?

Dr. Anand Vora:

Yeah, so we try to, opt for within the first six weeks, it's much more reasonable to get the two ends of the tendon pulled together. And again, the concept is the rubber band analogy.

We don't want to really go fishing far up to get one piece and then the other. So the sooner we can get to it, the sooner we can get the two ends together. In our literature, and personal experience has shown, we can still do that relatively reliably within the first six weeks.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Is there a such thing as operating too soon on an Achilles tendon?

Dr. Anand Vora:

So that that's pretty controversial topic, and my answer is that there's nothing wrong with operating too soon. If the soft tissue envelope, and the swelling is good. One of the difficulties is if we operate on the Achilles tendon too soon, sometimes it's difficult to find the layer around the tendon and repair it so that the surrounding area of the tendon has a good soft tissue envelope.

So we try to wait a little bit, but it's probably no such thing as too soon, or for that matter within the six week timeline, as long as the soft tissue is good.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

But it sounds like there's a sweet spot. Like you have to evaluate the soft tissue, but obviously you don't want to wait for a long time to have your Achilles tendon repair because then it just becomes more difficult, more complicated because of the separation of the ends.

Dr. Anand Vora:

Yeah. So ideally the sweet spot would be at one to two weeks out, within the timeframe of the rupture.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Let's talk about the day of surgery. When someone comes in for a procedure, what are your, um, pain management strategies? A lot of people are very intimidated by surgery, mostly because of the fear of pain.

And so what are some pain management strategies that you employ for an Achilles tendon patient?

Dr. Anand Vora:

So one of the nice things is that this concept of anesthetic with a regional block. By doing a nerve block, we can really prevent the significant pain that's associated with this procedure. The pain is usually associated with the surgical procedure within the first 24 hours.

And the nerve block really takes that variable out of the equation because patients don't have sensation in that area. The most important thing that we found is that elevation and compression really make a huge difference. One of the nice things at Illinois Bone & Joint, which we've pioneered is a concept of compression wrapping.

And that's a method that we use in combination with our physical therapists and all of our staff that allows patients to have their ankles wrapped in a device that allows for swelling resolution very quickly. And that's really minimized the need for pain management in terms of use of narcotics or other things.

Most of our patients take narcotics for a period of one or two days. And after that are taking simple, anti-inflammatories, keeping the foot elevated, and keeping the swelling down by wrapping it tightly.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Do you do anything in particular for blood clots?

Dr. Anand Vora:

The incidence of blood clots with the Achilles tendon surgery is a very, very controversial topic and incidentally, if we scan all of our patients that have had Achilles tendon surgery, 20% of patients will have a blood clot below their knee. However, that doesn't mean anything from a clinical standpoint, because these things are probably incidental, irrelevant, and they don't translate to major problems for the patients.

So it's very difficult, and it's a risk benefit strategy of, is it worse to treat the patient and put them on a blood clot medication? Or is it worse to have the very, very rare circumstance of something bad happening due to a blood clot? What we do in our practice is we use a low anti-inflammatory called aspirin that helps decrease the risk of blood clot, but still relatively safe and doesn't have the risks and side-effects of other blood thinners.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And so it's, it sounds like it's another individualized discussion that you have with patients about managing that very small, but present risk.

Dr. Anand Vora:

Correct.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Is there anything else that you would like to let the listener know regarding the Achilles tendon, the treatment of the Achilles tendons, the recovery from injury? Anything that you can add that would be helpful to our listeners?

Dr. Anand Vora:

Sure. I think the, uh, these tendon ruptures are important to understand, and they're very critical for our listeners to understand the role of operative and non-operative treatment and make sure they find someone that can help them guide through those options.

So they get a good informed decision on what they do. And then the other thing that is important is that the majority of the patients that we see are actually not patients with acute ruptures. Those are the patients that have this chronic degenerative change of their tendon. And that's more where the tendon simply becomes lengthened.

And it's like the rope analogy where the rope has become unraveled. And the good news about that for the listeners is that that responds very well to conservative treatment. Patients that have thickening of their Achilles tendon, we've learned that doing certain types of physical therapy protocols that are geared towards strengthening that tendon specifically–eccentrics, negatives–they strengthen the tendon more than they do the muscle. And using those types of protocols, patients can really do well and have improvement in their pain without any risk or very low risk for rupture.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

I consider myself a professional weekend warrior, um, who, like the best kind of weekend warrior for an orthopedic surgeon, because I rarely go out and do something. But then when I do it, I want to do it as hard as I can. It's a orthopedic stream. What should I be doing to avoid this Achilles tendon rupture? I feel like we've all been out on an athletic field, on a court where boom, someone goes down, they'll describe, oh God, someone hit me. They just struck me with a tennis racket or struck me with the basketball.

So again, it's not preventable. But some of the things that might lower the risk would be...

Dr. Anand Vora:

So our literature doesn't support anything that will lower the risk, but I'm going to tell you what I think Eric, and that is that unfortunately we all have to learn our limitations and we, as we get older, these things get harder and harder, myself included.

So I think it's very important, even if you're a weekend warrior– if your game is basketball or if your game is another sudden acceleration deceleration sport– tennis. It's also important to cross train and do other things. And so I think there's things not only just stretching, but things like yoga or things that also allow you to keep your muscle, your flexibility, your bones and joints healthy.

In addition to a muscular strength and having an ability to perform athletically, it's also important to take care of our bodies in all aspects, and incorporating all different types of cross training can be helpful

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Dr. Anand Vora, thanks for being a part of the IBJI OrthoInform podcast. And thanks for being with us today.

Don't Miss an Episode

Subscribe to our monthly patient newsletter to get notification of new podcast episodes.