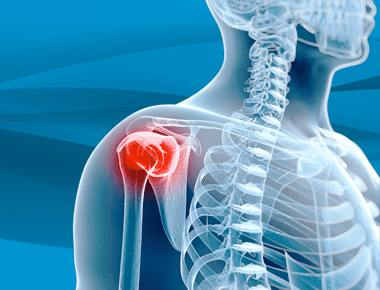

Shoulder Instability

Shoulder instability can be summed up as a failure of the components of the shoulder to stay centered in the socket. Learn more from Dr. Steven Chudik, Orthopedic Surgeon with Fellowship Training in Shoulder Surgery and Sports Medicine, about diagnosing and treating shoulder instability, and what to expect if you need shoulder stabilization surgery.

Hosted by Eric Chehab, MD

Episode Transcript

Episode 14 - Shoulder Instability

Dr. Eric Chehab:Welcome to IBJI’s OrthoInform where we talk all things orthopedics, to help you move better, live better. I’m your host, Dr. Eric Chehab. With OrthoInform, our goal is to provide you with an in-depth resource about common orthopedic procedures that we perform every day.

Today it’s my pleasure to welcome Dr. Steven Chudik, who will be speaking about shoulder instability. As a brief introduction, Dr. Chudik hails from Arlington Heights. He received his undergraduate degree from the University of Chicago and subsequently enrolled there at the Pritzker School of Medicine where he earned his medical degree in 1996.

He then began his residency training in orthopedics, at University of North Carolina Hospitals in Chapel Hill. Following the completion of his residency, Dr. Chudik did advanced specialty training in sports medicine and shoulder surgery at the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York City. Since 2002, Dr. Chudik has served patients in the Chicago area, specializing in disorders of the knee and shoulder.

As an innovator, Dr. Chudik holds six patents to advance the field of arthroscopy to treat complex shoulder conditions. As an educator, Dr. Chudik has founded the Orthopedic Surgery and Sports Medicine Teaching and Research Foundation. He has mentored scores of surgeons in training, he has also educated his peers and colleagues serving as a reviewer for research for both the Journal of Arthroscopy and the American Journal of Sports Medicine.

Dr. Chudik has helped thousands of patients return to their pursuits, from the budding athlete to the pro, and from the weekend warrior to the weekday worker. So Steve, welcome to OrthoInform, and thanks for being here today.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Thank you, Eric. It’s a pleasure to be here.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So we wanted to talk about shoulder instability, so let’s start with the basics. What is it?

Dr. Steven Chudik: Well shoulder instability is a big topic. I think a good way to start is to talk a little bit about anatomy. You know, the shoulder joint is made up of a bony ball on the top of your upper arm bone and a bony socket. The socket is kind of flat, so there’s not a lot of inherent stability to just the bones themselves.

So, there’s some other players involved as well. The socket has a soft tissue labrum that surrounds the socket like a bumper that helps provide some stability. And then there’s ligaments that go between the arm bone and this labrum and attach to the socket to provide stability, particularly when you get at the end ranges of motion.

And then, outside of this is a muscular envelope called the rotator cuff that helps compress the ball in the socket when we’re moving and doing activities. And, shoulder instability, to kind of sum it up is, is kind of a failure of these components of the shoulder to keep it centered in the socket. Either a structural failure of it that leads to dislocations, or it may be stretching or neuromuscular problems with it that doesn’t allow it to stay stable with certain movements that cause symptoms. And that’s kind of a broad view of shoulder instability. And we tend to categorize them into traumatic, meaning those would happen with injuries, and atraumatic, in the broadest sense. There are more complex areas and there are special concerns with throwers, with micro-instability. But I think it’s, for this conversation, it’s probably easier to talk about traumatic and atraumatic.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So let’s talk about an atraumatic shoulder instability patient. How do they typically present to your office?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Atraumatic shoulder instability patients don’t necessarily come in presenting with their shoulder coming out of place.

They tend to present with complaints of pain. They tend to be a younger patient, typically in their teenage years, often female. They usually have been subjected to a lot of repetitive overhead kind of sports. So, it’s typically a swimmer, a volleyball player, a pitcher, and over time they’ve developed pain in their shoulder.

They don’t know why. And it sometimes even continues into their activities of daily living. And then there’s some particular findings on them that are very consistent. They tend to be patients with loose ligaments and they tend to be double jointed kind of patients.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And how do you assess their double jointness? What do you do for that?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

When you’re evaluating someone young and you’re trying to diagnose this, a lot of it’s in the history, and it comes down to that type of patient who’s doing repetitive activities and then tends to present with ligamentous laxity, like you’re saying, and the best way to assess that is on physical exam.

And you can have them extend their arms at the elbow or try to extend their knee. And you’ll see that they typically go backwards. Other common ways to measure ligamentous laxity is to have them bend their fingers back or their wrist back. And they’ll usually be able to bend it quite far much further than most people would expect.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And then with, with traumatic instability, tell us a little bit about that and how that patient usually presents.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

The traumatic instability, it really comes down to the history. The patient is typically a contact athlete, they’re more likely to be male. Kind of in the ages of 15-30 or so. Rugby athlete, football player you know, they come in with a history, they said, you know, my shoulder popped out. The shoulder is one of those joints that the patient actually can really tell when they dislocate and they feel it and they can tell you. And often they had to go to the emergency room and someone had to put it back in for them.

And they usually come in in pain and it’s a very obvious and very consistent presentation.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So let’s talk about treating these when you have a patient coming in with atraumatic shoulder instability, what’s part of your evaluation? You said the history, the physical exam. Do you do any other testing?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Yes. I told you that the classic presentation and that makes most of the diagnosis for me, then you confirm it on exam with the loose ligaments. One thing I didn’t mention earlier is obviously we test the stability of the shoulder joint and they tend to have a very loose shoulder.

They have something usually called a Sulcus sign where you pull the arm down and you can actually see the ball, sublux below the socket and you see kind of a dimpling by the shoulder because their shoulders are so loose and can move so easily. Sometimes they can even demonstrate how they can move their shoulder in and out themselves.

But then what you’re getting to, I’m sure Eric is we tend to evaluate them with an MRI. Well, before that, I tend to treat them conservatively with therapy, but eventually if they don’t do well, then we evaluate structures with an MRI.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And then the traumatic instability person, that’s someone who presumably had their shoulder come out of joint, had it put back in, either by themselves or by someone helping them out in an emergency room or on the playing field or someplace. And when they come into the office, what are they like?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

They usually, if it’s been really close to the dislocation, are not able to really move the shoulder well. They’re often in pain and a sling. And so, they really don’t let you move them very well. On the other hand, if there’s been some time between the dislocations, these patients actually recover pretty well and may come in looking quite normal and on evaluation, they show apprehension signs.

Meaning, when you move their arm into the position where the dislocation is about to occur, they exhibit signs of apprehension either verbally, or they fight you and they hold back and they say, “it feels like it’s going to come out.” And, that’s a very classic finding that’s diagnostic for that type of instability along with that type of history, a traumatic instability.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So let’s move to the MRI with patients with atraumatic instability. A lot of the diagnosis has already been made by the history. This is the patient who comes in with pain, is an overhead repetitive athlete, has very loose ligaments, has that Sulcus sign where it looks like you can pull the arm out of the socket, and it dimples. What would you find on their MRI?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

At that point we’ve usually done a lot of conservative treatment that even contributes to the diagnosis, because we’d like to think there’s neuromuscular control there that we can sometimes overcome with lots of therapy, but when they fail that, you’re right. That’s when we get the MRI. And when we’re looking at that, we’re actually looking for structural damage.

We’re looking for labral tears, ligament tears, like that. But the classic finding is there was no injury. So, we don’t see any damage. We see a completely normal MRI. However, you will notice that they have a very loose, large capsular volume that’s very typical and consistent with their loose joints and loose ligaments.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And then what do you see in the traumatic instability patient who ends up with an MRI.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

So, in the traumatic instability, we always do the MRI right away because for the shoulder to dislocate, something had to be injured, and we need to know as part of the diagnosis and plan for treatment, what exactly happened. And, on the MRI the most common thing we’ll see is a tear of the labrum along with the ligaments off the bony socket. The ligaments can be torn off the humeral side. We can see in patients that have had more dislocations, or more traumatic dislocations, actually fractures to the edge of the socket of the shoulder joint, the glenoid. We also may see a dent or Hill-Sachs fracture to the ball of the humerus. And in older patients over 40, the rotator cuff is more susceptible, and we’ll often see rotator cuff tears. So, the MRI is a real crucial part of the initial evaluation of the traumatic instability patients who’ve had a dislocation.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So it’s good to think of these in terms of different mechanisms of injury, different presentations between the traumatic and atraumatic. And when you present the treatment options to a traumatic instability patient, how do you lay out their future? What’s the natural history of someone who’s experienced a traumatic dislocation? I think we probably have to divide it up into the young athletes, and then maybe the person over 40 or 50.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Yeah, I think that’s the way we need to look at it, because age is everything. When I’m talking to someone who’s had a traumatic instability or shoulder dislocation, it’s all about age and the riskiness of activities, and then obviously the extent of the pathology we’ve seen on the MRI.

So younger patients, less than 30, less than 25, typically have very, very high rates of recurrence. Some studies from 80 to 100 percent. And if they’re an athlete that’s young like that and actually plays contact sports, it’s closer to a hundred percent that they’re going to dislocate again.

And then, if the severity of the injury is just more soft tissue, there’s different options for repair. Obviously, if there’s fractures or things like that, it may warrant emergency surgery right away.

The older patient, those over 40. They tend not to re-dislocate. So, when they dislocate the first time, they often are amenable to rehab without surgery, as long as there is no rotator cuff tear. And, that’s the problem with the over 40 age group, even though they tend to be more stable after dislocation, they tend to tear the rotator cuff. And, if the rotator cuff is torn, that often warrants treatment.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Let’s go to the idea of surgery for these patients. We started with the atraumatic instability patient. We talked about their having normal anatomic structures, but they’re just very loose. So, what are the type of procedures that are available to that patient who has atraumatic instability?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

So, for all stability surgeries, there are open and arthroscopic approaches. Open is still done through smaller incisions, but often involves having to mess with the rotator cuff in one way or another. It has more morbidity, more stiffness, although higher rates of stability in some cases. I think what’s most popular in the United States, and I think most surgeons now have really moved to mostly all arthroscopic techniques because of it’s less invasive, early to recover.

We can actually see the anatomy better, like putting your eyes in the shoulder joint with arthroscopy. And then the procedure, particularly for the atraumatic, loose-jointed patient that’s having shoulder stability issues is going in there arthroscopically and decreasing the capsular volume.

Basically, you go in there and you shorten and tighten the ligaments to a certain extent, immobilize them for a period of time and let that tighten up. And then they restore their more normal range of motion, which I think gives them better biofeedback and neuromuscular control. It seems to resolve these pain issues and subtle instability as these patients have.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And then on the flip side with the traumatic instability patient, there’s a whole range of procedures that are available to them, but in general, can you discuss the types of procedures in broad terms.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

We have open and arthroscopic techniques. The open technique is a small skin incision. You open the deltopectoral interval between the muscles of the chest and the shoulder. But then, you get down to the rotator cuff that some people will cut off, that needs to be repaired, which hass a lot of morbidity. Some people can be a little slicker and make a longitudinal incision and spread it apart. So, you don’t really cut it off and it doesn’t need to be repaired or healed, which is much better and safer. Less morbidity.

And those procedures, though, are the open procedures do really, really well in maintaining stability, even in some studies may have a higher rate of stability and lesser rates of recurrence than the arthroscopic techniques, but they’re very close.

Arthroscopic techniques are done through very little, small incisions that we work through intervals, and we don’t have to cut any muscle. So, it’s a lot less invasive, and we can go in there and prepare where the labrum and capsule was torn off.

And then, sew the capsule and labrum back into place to retighten the shoulder. And, the same thing is done when it’s done open, but we can do that now with special instruments and techniques, arthroscopically.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So you’re describing the soft tissue procedure where the ligaments and the labrum get torn away from either the socket side or the ball side. And then when they’re torn away, the shoulder tends to go down that path. And we’re reconstructing it, so the path is no longer there. We’re repairing that, that loose part.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Correct.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

What are some of the other procedures that are effective for shoulder instability in the traumatic patients?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

So in Europe, the most popular procedure is actually something called the Latarjet, and it can be done open or arthroscopic, it’s mostly done open. And it’s actually where you take a piece of bone called the coracoid in the shoulder, along with one of the biceps muscles and tendons. That bone and tendon are actually transferred through a split in the rotator cuff and then placed against the socket with some screws to heal. And what it does is it makes the socket longer. So, it makes it harder for the ball to dislocate off that shelf. And, the tendon is thought to also make a sling when you get the arm in a position of dislocation that helps restrict it as well. That procedure has a lot higher success rate in terms of recurrences.

It doesn’t happen as often, however, there’s a lot more morbidity, a lot more complications, a lot higher rates of arthritis and not as popular in the United States for those reasons.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Yeah. I did hear that more recently, fellows coming out of training have been doing a lot more Latarjets here in the US, and yet we don’t know necessarily the long-term effect in terms of the rates of arthritis. We do know that it happens, and we’ve both seen some catastrophes that can happen with the Latarjet, from hardware failure, from the bone not healing when you’re making it bigger. But it’s an incredibly effective procedure at decreasing recurrence. But it comes at a cost, in my opinion.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

I would agree completely. It’s a very significant procedure that has a lot of areas where the graft could be malpositioned, screws can break, it may not heal, higher complication rate. And there’s no question. I agree. I’ve seen in my practice to a lot higher rates of arthritis.

So, it’s not something I’ve adopted. But there is no question that it does provide greater stability.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

There’s a role for it in the young athlete who’s had recurrent instability, who has bone loss, and we need to make the bone bigger and they understand that they’re robbing Peter to pay Paul. They want to be able to have a stable shoulder for their athletics now and will pay the price in the future and kind of accept that.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Yeah, it’s definitely weighing out the risks and the benefits and for those young athletes, particularly in contact, that have some bone loss on the socket, it doesn’t take much. It’s kind of like the tee in the golf ball. If you’ve got that golf ball and you just have a little chip on the end of the tee, the ball doesn’t want to stay in.

And, when you’ve got some loss of the glenoid bone, which happens usually with multiple dislocations or more traumatic dislocations, and they need something like the Latarjet, but it does come at a price.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

And now if we wanted to take the listener through what the recovery is like from a shoulder stabilization procedure, is there a big difference in the recovery from the soft tissue procedures that are done from the atraumatic or the traumatic procedures?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

I think it’s a very similar timeline. I think for the way I do it, I do it arthroscopically in the atraumatics, I do what’s called a capsular plication. I go in and I take tucks of the capsule and tighten it up with sutures arthroscopically, so it’s not very invasive.

And in the traumatics. I do it, again, arthroscopically, and it’s not as invasive. And, and so, you know, I think the first few days there was some discomfort and pain, I’d say most patients are able to get back to school or work within, a long weekend even, less than a week often. They’re in a sling, both of them, for six weeks to allow the tissues to heal and get some strength.

And then after that, we work hard to start getting the motion and strength back while the repairs of the capsule and ligaments start to mature and get stronger as well. So, we don’t like them to go back to risky activities, not for a while. The fortunate or unfortunate thing is that these young patients, because the arthroscopic procedures are so less invasive, by two and a half, three months, they feel spectacular.

I had one 6’5″ scholarship pitcher who was shooting three pointers at three months after stabilization, like, what are you doing? But you have to be careful.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

They feel well enough to do it, which is a bonus and also a curse because what else is going on?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Right. Well, we still got to wait for healing. Those ligaments that we repaired are still maturing and still healing. And if they’re doing too much, they may not let that heal.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

How long does that maturation process take?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

I think in my practice, I think it’s gotta be closer to the six-month mark and I don’t let people get back to contact sports until that range. I do see people getting back to most of their activities by four months and even non-contact athletes to some sports at that point, but the contact athlete rarely before six months.

And then if you have an overhead thrower or athlete like that, to really get the shoulder in shape to throw, which is one of the most demanding things on the shoulder, it really takes more like nine months and even on a professional level could be up to a year, but I usually shoot for about nine on those people.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So just to summarize, not too big a difference for the surgical procedures that are done for the traumatic and atraumatic instability patients. Usually in a sling for about six weeks to allow the soft tissues to heal. They’re feeling pretty good. Maybe arguably too good, by three months, and then, but really with the mature, repair ligaments back in place, ligaments performing the way they’re supposed to at about five to six months after the procedure.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

I would agree with that.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

What do you see more of? Do you see more of the atraumatic instability or the traumatic instability patients?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

In my practice, I definitely see more of the traumatic. It’s just like the ACL, it’s really become quite an epidemic of an injury with these young athletes. Especially with the contact sports, I think each year I keep seeing more and more traumatic shoulder dislocations.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Yeah. I think part of it’s the specialization within sports. The repetition, I think even as it plays a role.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Repetition and exposure, they’re just out there that more commonly and exposed to those potential injuries.

And we didn’t mention about the older groups. So, the atraumatic instability and the loose-jointedness, we only really see in that subset of that young age teenage group, typically. We could extend a little bit sometimes in some females, but not too often– but traumatic instability we see at all ages.

And just as patients get older, the tissues are less robust. A 25 year-old that dislocates his shoulder, never tears his cuff, but if you get over the age of 40, the incidence of rotator cuff tears become pretty common. As you get older, then we start to see more fractures. So, we also do see commonly, and it’s more so from falls than it is sports, but still some athletes.

And those injuries seem to be more severe in terms of bony damage and rotator cuff and then often need earlier surgery because of those issues.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

In wrapping this up, we have the traumatic and atraumatic instability patients. We have the young and old patients. We try as the treating physician to figure out what was the mechanism was an, a traumatic mechanism, a traumatic mechanism, because they are treated differently, and the anatomic structures are different as a result. But how do we do? Are we pretty successful with these procedures?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

I would say overall, we are pretty successful. I think on the atraumatics, there are some patients I think just have some genetics and some very loose collagen that tends to stretch out, that I always worry about. It stretched out for them doing these other activities. After I tighten it up, can it happen again?

I’d have to say the majority of the patients I’ve seen over the years, they haven’t, they’ve done typically very well. I’ve had a very low recurrence rate of pain and symptoms that they have. But there are some people out there that I think just their collagen is just not as durable or it likes to stretch out, that I think it can recur. But again, after they get to a certain age group and they’re less active over 20, it seems to resolve on its own.

So we usually can get them through that period of time, just fine. So I think the success rates are really great there.

On the traumatic side, it varies a lot on the age and the extent of the pathology and whether they’re a contact athlete or not. The younger they are, the higher the risk of the recurrence. The number of dislocations they’ve had before they have surgery even increases the rate of failure.

So, I like to operate on them earlier, before they get more pathology and things get worse. And with more dislocations, you get more bone erosion, more problems like that, that have led to what we’ve been finding is more rates of recurrence.

I would say that on average, the percentage is less than 5% for re-dislocation, could be 2-3% in some groups. But when you start getting into the contact athlete, the rates go up to sometimes 15%. And there’s been some recent studies, even in rugby players, up to be 50%.

I haven’t seen that, but there’s no question, there’s kids that you worry about them going back. I think there’s a lot of ways we need to think about addressing that going into the future.

And I think there’s some things coming down the pipe to address that problem. Cause this operation isn’t perfect. These kids can tear it out when it’s normal and they can tear it out after it’s repaired. And I explained that to them and we maybe sometimes should be mentoring them to not go back to these contact activities as much.

And that’s sometimes better than doing a Latarjet or a bony procedure with screws and bony anatomy-altering surgeries that we know are going to develop a lot of arthritis a lot earlier.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

So, you hold six patents on shoulder instruments and you have an innovative technique for doing a socket expanding procedure that’s different than the Latarjet. Can you describe that?

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Sure. About 15 years ago, the president of the Chicago Rugby Association came to me from a well-known institution, and good surgeons, and had two failures of arthroscopic Bankart repairs. And it was before we were really thinking about bony anatomy.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

The Bankart being the soft tissue repairs, where you sling the ligaments.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Yeah. Thank you for, for clarifying. Yeah. And on further evaluation, we’ve got a CT scan and it showed that he was missing about 25% of his socket.

And so, no matter how many times you repaired the soft tissue, that ball wasn’t going to stay in place. And he wanted to keep playing rugby and doing those activities. At the time, I had the Latarjet procedure as an option, I wasn’t that comfortable with it. At that time, especially in America, it was new for us, and there was a lot of complications associated with that stuff.

And I felt I could do it arthroscopically. I really didn’t like t.e open approach. There was a technique of using some bone from the hip. And so, I decided, well, I bet I could find a way to get that into the joint and fix it there. And I, with a company, designed some instruments, and we developed this procedure and were able to transfer a part of his own type of bone, which heals the best, into the socket and restore the full socket that was missing and broken. And then repair the soft tissue over this fresh bone to allow that to heal and restore the ligament stability.

And, and that procedure has worked very, very well for him. He went back to all kinds of overhead athletic sports and tackling sports and lifting weights. And, and I’ve continued to do it over the last 15 years. Fortunately, it’s not that frequent that I need to do that, but I found it to be very effective and I haven’t actually had a patient re-dislocate. It’s very good for stability.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

That’s really great. And then there was another innovation you had in terms of trying to assess when someone is ready to go back to sports. That’s probably the most difficult thing that any of us face as treating physicians or treating physical therapists. When is someone truly ready to go back? So tell us a little bit about that.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Yeah, you know, I kind of took this from our thinking in the ACL. With shoulder stability, we’ve always thought it had to be a stronger repair. With ACL’s we learned, the stronger the ACL didn’t always protect it.

It had to do a lot more with the mechanics of the patient and the neuromuscular control. And you could actually train patients to land and cut better and lower the incidence of reinjuries or tearing their ACL. And I’ve done some research in that area and we even developed a test that people pass or fail, and it showed that if you pass this test, you’ve a lot less likelihood of re-injuring it. So, we decided in thinking about it, why does the shoulder work so much differently than the knee?

And so, we developed a kind of a dynamic stabilization program, so it helps train the patients to maintain better stability of the shoulder with their own neuromuscular control. It’s a bunch of additional exercises beyond therapy, a lot of walking on your hands and strengthening that way. I got a little ideas from that, taking care of some division one athletes that did some of that kind of work and seemed to do a lot better with stability than did some of the high school athletes that didn’t have those resources.

And then from that, we said, well, we had a test for the ACL. Let’s do a test for the shoulder. And so, it measures your strength and stability in a way that we haven’t been able to prove and research yet, like we had the ACL. But hopefully, with more and more patients be able to show that this test works and when someone passes it, I can tell them that they’re likelihood of dislocating again will be a lot less.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Yeah.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

We’re hopeful.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

That’s great stuff. I mean the neuromuscular training for the knee injured athlete is so important, and I don’t think people really understand that the risk reduction of about 50%–

Dr. Steven Chudik:

That’s huge.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

It’s a big number. And if we can get something similar to that for the shoulder, again, to not have these injuries recur, would be the best thing for us as providers and obviously way, way better for the patients.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

For sure. For sure. I agree completely Eric.

Dr. Eric Chehab:

Our guest today is Dr. Steven Chudik of Hinsdale orthopedics, a division of Illinois Bone and Joint. Steven, thanks for being here.

Dr. Steven Chudik:

Eric. Thanks for having me, it was a great talk.

Don't Miss an Episode

Subscribe to our monthly patient newsletter to get notification of new podcast episodes.